Designing Conveyor Guarding for Compliance, Safety, and Practical Operation

Conveyors are widely used across processing, manufacturing, and materials-handling environments, but they also present some of the most persistent safety risks in industrial operations. Entrapment, nip points, rotating components, and maintenance access are all recognised hazards that must be managed through proper design and guarding.

In Australia, these risks are addressed through AS 1755 – Conveyors – Safety Requirements, which establishes the minimum safety expectations for conveyor systems across their full lifecycle, from design and installation through to operation and maintenance.

This article outlines what AS 1755 requires, why compliant conveyor guarding is critical, and how engineering-led design plays a key role in achieving practical safety outcomes.

What Is AS 1755?

AS 1755 is the Australian Standard that defines safety requirements for belt conveyors and other conveyor systems. It addresses both new and existing installations and applies to conveyors used in industrial, commercial, and processing environments.

Rather than focusing on individual guarding components in isolation, AS 1755 considers the conveyor system as a whole, including how people interact with it during normal operation, inspection, cleaning, and maintenance.

The standard is referenced by regulators, safety professionals, and engineers as the primary benchmark for conveyor safety in Australia.

Key Safety Principles in AS 1755

AS 1755 is built around a number of core safety principles that influence how conveyor guarding should be designed.

These include eliminating hazards where possible, controlling remaining risks through engineering solutions, and ensuring that guarding does not introduce new risks by restricting access or encouraging unsafe behaviour.

In practice, this means that compliant guarding must be effective, durable, and suitable for the operating environment, while still allowing conveyors to be inspected, cleaned, and maintained safely.

Conveyor Guarding Requirements

A major focus of AS 1755 is the control of access to hazardous areas. This includes guarding of:

- Drive pulleys and tail pulleys

- Return rollers and idlers

- Nip points and shear points

- Rotating shafts and couplings

- Chain drives, belt drives, and gearboxes

Guarding must be designed so that body parts cannot access hazardous zones, taking into account reach distances, openings, and the position of the conveyor relative to walkways or platforms.

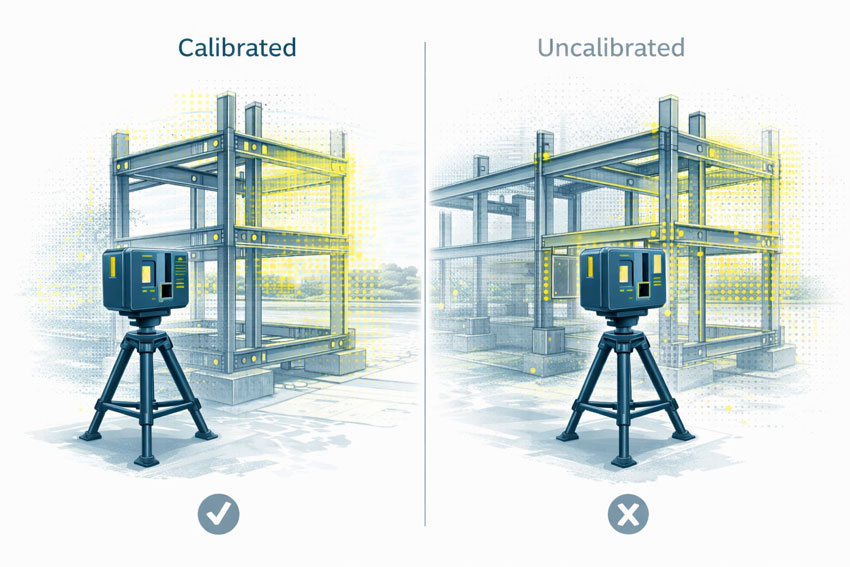

Importantly, AS 1755 recognises that guarding must be fit for purpose. Poorly designed guards that are difficult to remove, inspect, or maintain are often bypassed or removed altogether, creating new safety risks.

Fixed Guards vs Interlocked Guards

AS 1755 allows for different types of guarding depending on the application and risk profile.

Fixed guards are commonly used where access is not required during normal operation. These guards must be securely fixed and require tools for removal.

Interlocked guards may be required where regular access is necessary. These systems ensure that the conveyor cannot operate while the guard is open or removed, reducing the risk of exposure to moving parts.

Selecting the appropriate guarding strategy requires an understanding of how the conveyor is used in practice, not just how it appears on drawings.

Existing Conveyors and Retrofit Challenges

Many conveyors currently in service were installed before the latest versions of AS 1755 were adopted. In these cases, compliance is often achieved through retrofit guarding rather than full replacement.

Retrofitting guarding to existing conveyors introduces additional challenges, including:

- Limited space around existing equipment

- Incomplete or outdated drawings

- Structural constraints

- Ongoing operation during upgrades

Engineering-led assessment and accurate documentation of existing conditions are critical when designing retrofit guarding solutions that comply with AS 1755 without disrupting operations.

The Role of Engineering in Conveyor Guarding Design

AS 1755 does not provide prescriptive “one-size-fits-all” guard designs. Instead, it sets performance requirements that must be interpreted and applied by competent professionals.

Engineering input is essential to ensure that conveyor guarding:

- Addresses all relevant hazards

- Integrates with existing mechanical and structural systems

- Can be fabricated and installed accurately

- Supports safe maintenance and inspection activities

Poorly engineered guarding may appear compliant on paper but fail in real-world use.

Documentation, Verification, and Ongoing Safety

Compliance with AS 1755 is not a one-time activity. Conveyor systems evolve over time as layouts change, equipment is upgraded, and operating practices shift.

Clear documentation of guarding design, installation, and assumptions provides a baseline for future modifications and safety reviews. This documentation is also critical when demonstrating due diligence to regulators or during incident investigations.

Why AS 1755 Matters

AS 1755 exists to prevent serious injuries and fatalities associated with conveyor systems. When applied correctly, it provides a structured framework for identifying hazards, implementing effective controls, and maintaining safe operation over the life of the equipment.

Achieving compliance requires more than installing mesh around moving parts. It requires understanding how people interact with conveyors and designing guarding that supports safe behaviour rather than working against it.

Conveyor guarding designed in accordance with AS 1755 is a critical component of safe industrial operations. Engineering-led design, accurate documentation, and practical consideration of maintenance and operation are essential to achieving compliance that works in practice.

When conveyor safety is treated as an engineering problem rather than a checkbox exercise, the result is safer equipment, fewer incidents, and more reliable operations.

Our clients